Shigeru Mizuki (manga author) maybe well-known for stories of Yokai (Japanese spooky monsters, trolls and other supernatural creatures), but I have only ever read his war stories. Mizuki himself served in the Japanese Imperial Army and just about survived (not in one piece though, he lost his dominant left arm), and his rage about the tragedy of war and the wasteful deaths of countless soldiers is only readily apparent in the semi-autobiographical Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths.

Hitler (published in English in 2015) is another such work of the more serious gekiga (dramatic pictures) tradition as opposed to the more whimsical manga (which does cover a wide range of genres that don’t really seem all that whimsical—history, drama, science-fiction, in addition to the fantasy genre that many associate it with). According to Wikipedia, gekiga is “akin to Americans who started using the term ‘graphic novel’ as opposed to ‘comic book'”. I think the exact differences between this comparison, and indeed, between a graphic novel and comic itself is open to debate. Another master, Osamu Tezuka, also experimented with the darker gekiga. I’ve read Message to Adolf, coincidentally also having to do with Hitler, but a fictional political thriller very different from Mizuki’s Hitler.

Serious or not,

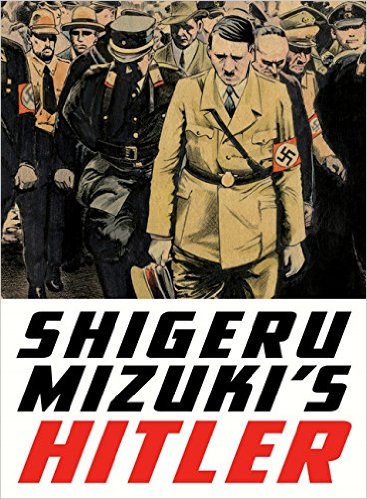

…Shigeru Mizuki’s Hitler…shows his signature combination of realistic, high-contrast backgrounds traced from photographs, and characters drawn in a cartoony style. Humans are rarely beautiful in Mizuki’s world: they usually appear as loopy, lackluster characters, acting as misshapen as they look.

– From the introduction to Hitler by Fredrik L. Schodt, noted scholar in manga and anime.

In Hitler, the cartoony humans look mostly goofy and grumpy—bad-tempered, angry, depressed, morose, or tormented. With the exception of the cover, where Hitler looks as realistic as the background, the great dictator is usually either comically enraged or woefully miserable inside the book.

Mizuki’s focus is on Hitler, the person, and not on his role in the Holocaust. Through his detailed portrait and comprehensive notes, Mizuki covers Hitler’s beginnings as an impoverished and not particularly talented art student, his winning the Iron Cross, and traces his political career that seems to be driven by some strange destiny: his joining the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) which came to known as the Nazi Party, the Beer Hall Putsch, his close relationship with his half-niece Geli and her subsequent suicide which supposedly left him a broken man, the Night of the Long Knives where Hitler purged his enemies and cemented his authority, the rousing speeches and political maneuvers that led to the rise of this former vagrant to Chancellor and later Fuhrer of Germany, his role in the War, and his final downfall.

With his trademark toothbrush mustache, hair slicked back with pomade, Mizuki depicts in Hitler a melodramatic patriotism (“my pains are nothing compared to the wounds suffered by my beloved Fatherland”, Hitler weeps), megalomania (“I am swelling with talent”, he claims mournfully), and a deep-rooted anti-semitism, without delving much into the Holocaust itself.

“I am poor and unpopular. This is entirely the fault of the Jews…Thousands of bowlegged Jews invade our land like an army. They tempt and steal our women. I boil for the sake of all German woman”, Mizuki’s Hitler rages to his landlady.

“Jews are the lowest of the inferior races. You know that”, he tells a virtually imprisoned Geli whom he discovers with a boy he presumes to be a Jew (“You don’t need to say his name. I know he’s Jewish”). “Even one kiss taints a woman forever. You’ll be Jewified. Understand?” Her “betrayal” is compounded by the coming true of his greatest fear: a Jewified Geli.

Furthermore, Hitler squarely blames Germany’s depression, unemployment, hunger and poverty on the “global Jewish conspiracy”.

The Nazis promise a sense of belonging and escape from this economic hole, as well as the chance to blame someone else. People flock to the banner.

Hitler ends with Hitler’s demise, and his gift to Germany—a country in ruins.

What was the significance of Mizuki’s focus on this one person in particular?

My destiny would have been different. In other words, I would have avoided my wretched life in the military, and I might still have my arm. So how could I not be interested in Hitler, and in knowing what sort of a man he really was?”

Schodt writes further that:

But in a darkly humorous style only Mizuki can pull off, we see Hitler as a very ordinary human, who through a historical fluke, assumes power over his nation and leads it to ruin…at the core, he was just a miserable human. And because he was human, it’s important for us to know him as such. There are Hitlers in every era, culture and ethnic group, and perhaps deep inside all of us. Best then, to know them, and know them well.